Labour’s tax raid on the UK’s North Sea oil and gas producers risks leaving taxpayers on the hook for billions of pounds more in decommissioning charges than first thought, analysts have warned.

Rachel Reeves’s decision to raise overall taxes to an astonishing 78pc, the highest of any sector, and strip the industry of tax allowances will drive down profits so fast that some smaller companies will run out of cash for clean-ups, says the report.

The warning comes from highly-respected industry analysts Wood Mackenzie, and follows Ms Reeves’s pre-Budget pledge to raise oil and gas production taxes for the fourth time in two years.

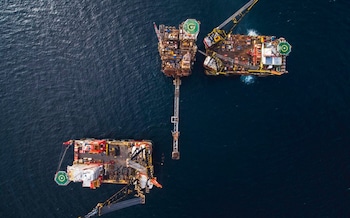

The price tag for decommissioning the North Sea’s infrastructure, which includes dismantling pipes and filling old wells, has always been high – but Ms Reeves’ tax raid threatens to put even greater strain on the companies responsible.

That is raising questions over whether the industry can still afford it, and if British taxpayers will be on the hook if they can’t.

The industry looks under greater strain because it faces an increased windfall tax and the loss of the 29pc investment allowance that accompanied it, plus cuts in capital allowances.

Wood Mackenzie warns in a report that some firms will collapse under such massive levies.

“This scenario would wipe-out £19bn or 65pc of capital expenditure, halve UK production by 2030, and all but eliminate industry cash flows by the 2030s.

“The reality could be even worse. Smaller companies would likely fail through lack of cash flow, with implications for partners and the UK Government,” it says in the report.

One consequence, Wood Mackenzie warns, will be that many companies run out of cash for decommissioning.

“Without capital allowances between now and 2030, a new tax regime after that will be irrelevant for many.

“With next to no cash flow smaller companies will succumb, and could default on their decommissioning liabilities with implications for partners and the UK taxpayer.”

International treaties oblige offshore operators to remove disused platforms and pipelines, and fill old wells with cement.

A single unplugged borehole can release tonnes of toxic oil and methane, a potent greenhouse gas. However, plugging each well costs £8m, and oil and gas companies are increasingly reluctant to pay for it. This has caused an expensive backlog to build up.

Offshore regulator the North Sea Transition Authority’s latest “Well Insight” report showed there were 2,165 wells planned for decommissioning by the early 2030s at a cost of £24bn.

It has sent warning letters to operators about the 740 it is most worried about and opened investigations into missed deadlines. It is also proposing to name the worst offenders, including publishing a league table to shame them and alert investors.

But analysts say the new taxes imposed on oil and gas are a key cause of the growing backlog because they are stripping out the profits that would otherwise have financed decommissioning.

The same taxes, plus the Government’s ban on licensing new oil and gas fields, mean investment in production is also plummeting.

“Having stated it believes UK oil and gas must be kept healthy and productive ‘for decades to come’, the Government is creating an investment environment where the industry is fatally wounded in less than five,” says Wood Mackenzie.

The UK consumes about 70bn cubic metres of gas a year, of which about 32bn comes from the North Sea.

Industry experts predict at least 180 of the UK’s 283 oil and gas fields will shut down by 2030, cutting gas output by 70pc by 2030 under the current tax regime – leaving the UK even more reliant on imports.

But as fields shut down prematurely they will also become liable for early decommissioning, meaning companies will see once profitable assets turning into expensive liabilities much earlier than expected.

Taxpayers are already liable for a large chunk of this money.

A 2023 study by Offshore Energies UK (OEUK), the industry trade body, put the total cost of decommissioning at £44bn by 2063 – with taxpayers on the hook for at least £14bn in the form of tax rebates.

This is because the Treasury has long agreed with the industry that decommissioning costs are a business expense, offsettable against previous years’ profits.

Even these sums could be an underestimate: OEUK predicts industry decommissioning costs of £2bn a year by the early 2030s.

But analysts say the new taxes mean all these costs are likely to increase because of fields shutting down prematurely and so needing early decommissioning.

Research by Stifel, an investment bank, predicts decommissioning costs will now be brought forward by a decade and could exceed £3bn a year by 2032 – up to 50pc above previous estimates.

That means tax rebates to oil and gas companies will grow sharply too, eventually exceeding the tax generated by oil and gas profits.

Chris Wheaton, author of the Stifel report, says that in such a scenario, “decline accelerates decommissioning – and once decommissioned, fields can’t be resurrected”.

“From around 2040, repayments of historic tax paid towards decommissioning costs could exceed tax generated from the industry,” he adds.

If companies responsible for decommissioning also default then that would add even more to the cost imposed on taxpayers.

Sonya Boodoo, of energy consultancy Rystad, says: “Companies do not feel confident making substantial investment decisions under a constantly changing regime, so we expect activity on the UK continental shelf to take a hit in coming years.

“If no new fields come on-stream, production in the UK could decrease by one-third from 2023 levels. This would have dire consequences for the UK oil and gas industry.”

The ban on new drilling means many companies are leaving UK waters, says Sam Long, chief executive of the industry trade body Decom Mission.

“The UK is particularly exposed to the withdrawal of mobile offshore drilling rigs. The lack of development work, drilling new wells, plus the industry-wide underspend in well abandonment make the UK unattractive in comparison to the Middle East and Norway.”

The growing shortage of drilling rigs, the offshore units which both drill wells and decommission them, is also driving up prices.

Ashley Kelty, analyst at Panmure Liberum, says: “The Wood Mackenzie report has delivered further proof of what people in the oil and gas industry, advisers and market analysts have been saying for some time.

“I would agree that insolvencies could see UK taxpayers on the hook for costs of decommissioning, which will vastly outweigh any additional revenues generated.

“But the bigger concern is the apparent lack of understanding by the Government on the concept of energy security, with Energy Secretary Ed Miliband appearing to be hellbent on destroying the oil and gas industry.”

Wood Mackenzie’s report reaches a similar conclusion – albeit couched more diplomatically.

“At this very late stage of maturity, the UK oil and gas sector requires careful handling and stability if it is to remain sustainable for the decades the Government believes the country will continue to need oil and gas supplies,” it says.

A Treasury spokesman says it works with Mr Miliband’s Department for Energy Security and Net Zero and the NSTA to monitor the financial health of offshore operators and reduce the risk to taxpayers.

“We are committed to maintaining a constructive dialogue with the oil and gas sector to finalise changes to strengthen the windfall tax, ensuring a phased and responsible transition for the North Sea.”

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.