Most of us use olive oil every day, splashed in a pan, trickled over a dish of hummus, mixed into a salad dressing. No wonder – it’s not just delicious but good for you too. Olive oil is the bedrock of the Mediterranean diet, the most scientifically backed eating plan for good health.

A study in the US indicated that eating as little as one teaspoon (five grams) of extra virgin olive oil daily could reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease, the leading cause of death worldwide.

But can you trust that the bottle in your kitchen is the real thing? It’s certainly costing enough. Olive oil prices are soaring: they are up a third on last year alone, following a 36% drop in yields from the main olive-producing countries, chiefly because of the dual scourges of Xylella disease and heat waves driven by climate change.

All this has led to a rise in fraud in the EU. In July this year, £750,000 worth of fake olive oil, suspected of being coloured green with chlorophyll, and labelled as “extra virgin” was seized in Puglia, south Italy.

Although you’re highly unlikely to buy a fake olive oil from a reputable shop in the UK, producers may sail close to the wind when it comes to categorisation. Extra virgin olive oil (EVOO), the kind that is the highest in beneficial compounds including antioxidants, degrades with time, and faster if it is poorly stored.

“You might buy a bottle of extra virgin olive oil that may have left the producer fulfilling extra virgin criteria,” says Simon Poole, a NHS doctor and author of The Olive Oil Diet, “but may, after several months on a supermarket shelf,…no longer be extra virgin.”

This is particularly possible if, as is common, the oil only just scrapes in as EVOO at the time it is purchased from producers by the big olive oil brands.

Oxidisation, caused by heat, light and exposure to air, is the chief degrader of olive oil, spoiling the flavour, raising the acidity and reducing its healthy properties as the antioxidants are consumed by oxygen.

So how can you be sure your EVOO really is extra? Here’s a guide to getting the good stuff.

What you should be looking for in EVOO

Label

Just because the label looks Italian, doesn’t mean it is Italian: if you want to know where your olive oil is from then scrutinise the small print. Chances are it’s a blend from EU countries. Single origin from Greece or Turkey is excellent and may be better value than Italian.

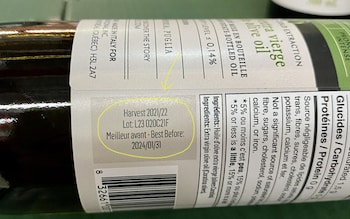

Look for a date of pressing, and try to buy oil that’s a maximum of 15 months old from a shop with a high turnover. If the best before date is all you have to work with, it’s likely to be 18 months after the pressing date. For the highest beneficial compound levels, look for specialist brands, such as Odysea’s Good For You Polyphenol Olive Oil (£8.50 for 250ml, sainsburys.co.uk).

Packaging

Light speeds the oxidation of olive oil so it’s important to pick one that is sold in a darkened glass bottle or a tin.

Colour

Colour generally indicates olive type, ripeness, and level of filtering rather than quality, so good oil can be deep green or golden yellow. Olive oil assessors use blue glass cups to taste so they aren’t influenced by the colour, as it’s said that greener oils tend to be grassier and more fruity, while yellower oils tend to be spicier. However, those deep emerald oils turn yellow if exposed to light and heat – a bad sign – so a green colour can be reassuring.

Smell

This is a much more reliable marker of quality. Giovanni Quaratesi of olive oil importers Certified Origins advises pouring a little bit into a cup, covering it with your hand and letting it warm to at least room temperature. Lift your hand and sniff: “if you smell …freshly cut grass, fruit, veggies, anything that is very fresh and alive, that’s a great sign.”

Flavour

Look for flavours of ripe green fruit or grass, but also a slight irritation, a tickle at the back of the throat. Many of the beneficial compounds, says Poole, are produced by the plant “as a defence mechanism…slightly bitter and pungent to put mammals off eating them before they’re ripe.” There should be no trace of rancidity though.

Viscosity

EVOO is thicker than most oils, and the lower the oxidation levels the higher the viscosity, however this is hard to measure without specialist equipment. Monounsaturated fats, the chief component of olive oil, thicken at a higher temperature than polyunsaturated (the type of fat in many vegetable oils) so it’s sometimes said that if a bottle of olive oil solidifies in the fridge, it is proof of good quality. However this isn’t always the case: the fatty acid content of oils varies widely and other oils (such as peanut) will also solidify when chilled.

Olive oil storage

The worst place you can keep your olive oil is in a big clear glass container by the cooker. Heat, oxygen and light degrade oil, so if you must keep some next to the hob, decant some into a small opaque bottle and store the rest in a cool cupboard.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.