Mary McFadden, who has died aged 85, was a much-married American socialite who, by her own account, “fell into fashion backwards” in the 1970s, turning her fantasies of ancient civilisation into a multi-million-dollar clothing business.

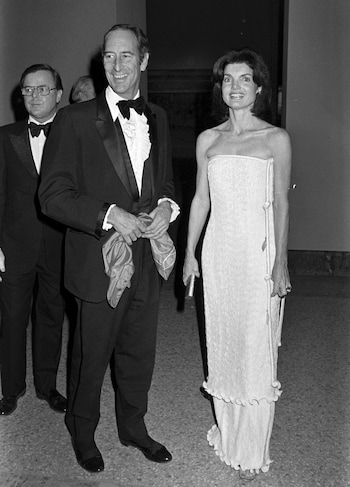

Prized by society women of a certain age, notably Jackie Onassis, Estée Lauder and Dame Margot Fonteyn, her clothes were sophisticated rather than “sexy”, epitomised by the pleated column dress, which gave its wearer the air of a Grecian statue.

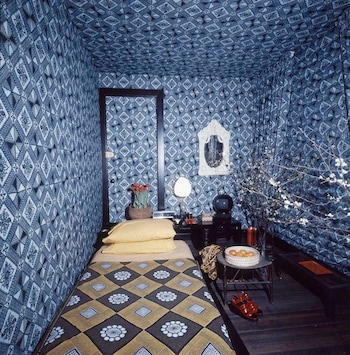

Mary McFadden was duly nicknamed “the high priestess of fashion”, and her chalk-white face and ebony bob lent her the intimidating aspect of an enchantress. But her sensual, timeless clothes kept cannily on the wearable side of avant-garde, and she was credited by Vogue with changing the way women dressed in the 1970s and 1980s: “Though not hippie-ish in the least, they tapped into the prevalent fantasy of other places and other times.”

Her signature pleats were achieved by a patented seven-step heat-treatment of satin-backed polyester, a fabric she staunchly defended even when the tide of fashion turned against it after the excesses of the 1970s. Polyester may have been “cheap-looking,” she said, “but when I pleated it, it fell like liquid gold on the body.”

This enabled her to emulate the famous 1920s micro-pleated silk of Mariano Fortuny and his wife Henriette Negrin, whose precise method remains a mystery. Karl Lagerfeld would later accuse Mary McFadden of being derivative, bitchily claiming that her debt to Fortuny was so great “she should single-handedly pay for the restoration of the Fortuny palace”. But she denied that Fortuny had a monopoly on the concept of the pleat, which was simply “the height of classicism” and would be revived in every period because it “disguises the mountains and the valleys of the figure”.

Mary Josephine McFadden was born in Manhattan on October 1 1938 and brought up with her two younger brothers on a plantation near Memphis, Tennessee.

Her Philadelphian father Alexander “Billy” McFadden had fought with Merrill’s Marauders in Burma in the Second World War, and came from America’s second-biggest cotton-merchandising family. He was parvenu, however, compared to his wife Josie, née Cutting, a concert pianist and chilly New York socialite descended from one of the drafters of the Declaration of Independence.

Mary McFadden described herself as “the ugly daughter of a beautiful mother”, and her mother’s palpable disappointment in her was thrown into relief when her father was killed in an avalanche when she was nine. The family moved to Long Island, where her mother married a gentleman golfer, quickly to be replaced by a millionaire banker, and packed Mary off to summer in Europe until she found something interesting to say.

As a consequence, Mary’s approach to life, and later fashion, revolved around getting attention. She played tennis on the junior professional circuit and trained for the Olympics ski team. At 14 she died her hair silver. After finishing school in Paris, she studied design in New York but dropped out to work as Christian Dior’s public relations director, while dating Oscar de la Renta.

In 1964, however, she married Philip Harari, a DeBeers executive, and moved with him to Johannesburg. The marriage produced a child but lasted only a year, after which she found work at South African Vogue, thanks to her friend Diana Vreeland, and built herself a sprawling Palladian garden using convict labourers with a Zulu overseer. When South African Vogue folded, she moved to the Rand Daily Mail, where she had a column, “Mary Quite Contrary”, but her stories on native tribes were “not exactly appreciated by the government”, she observed.

In 1968 she moved to Southern Rhodesia with her next husband, the museum director Frank McEwen, 35 years her senior and “a major god in Africa,” she recalled. “He had taken black artists and made them into gods. And he looked like Francis I.”

She began to make togas and tunics inspired by Masai and Ethiopian dress, and founded a sculpture workshop in the bush, but when McEwen announced his intention to spend the next 10 years at sea “without touching land”, they divorced and in 1970 she returned to New York.

Her next boyfriend was J Patrick Lannan, a playboy whose attention she captured by informing him that 80 per cent of his African art collection was fake. He helped to launch her fashion business in 1973, starting with quilted print jackets and flowing garments from her hoard of African textiles.

Soon her collections ventured into any place or period that caught her fancy: pagan Rome, Isfahan, Renaissance art, the convent life, Mexico’s Olmec period, the Napoleonic Wars or the paintings of Ingres. “Surely it is not too much to say that McFadden has proved that she deserves to be ranked among the fashion world’s most superb artists,” wrote one critic.

By 1976, her gross sales were $2 million. She went on to win two Coty awards (fashion Oscars) and became the first female president of the Council of Fashion Designers of America. She also contracted a brief third marriage to an unstable man who “looked like a Greek god”, in addition to liaisons with the publisher George Weidenfeld and the jeweller Kenneth Lane.

But her individuality was also her undoing. She boasted that she was immune “to the ‘isms’ of the day”, but she could not reinvent herself sufficiently radically to stay afloat in couture. By the start of the 1990s, it was reported that “her clothes are as predictable as her hair colour. Though a McFadden gown still represents a certain status (three or four turned up at the recent White House dinner for Queen Elizabeth)… the pleated dresses haven’t changed much. ‘We stopped carrying her line a few seasons ago,’ says a buyer for a major department store. ‘Nobody even noticed.’”

She got her name back in the press in 1989 when she announced, aged 50, her fourth marriage to a 22-year-old design student, Kohle Yohannan. She milked tabloid attention in their on-and-off romance for a good two years, at one point characterising him as a “cheap toy-boy”, “a spaced-out delinquent” and “a complete flake”, although they remained friends.

She closed her ready-to-wear business in 2002, but her clothes retained a cult following, fetching high prices secondhand.

A sixth (or seventh, depending on accounts) marriage, to the 31-year-old director Vasilios Calitsis in 1996, also ended in divorce. She would later claim to have been married 11 times, although some of these were “only spiritual”. Her partner until his death in 2019 was Murray Gell-Mann, the 1969 Nobel laureate in physics.

Her daughter by her first marriage died in 2023.

Mary McFadden, born October 1 1938, died September 13 2024

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.