You are Henry Tandey, a British soldier in the trenches of the First World War. You are about to go over the top and attack the German trenches but you’re a career soldier and know the risks. You’ve fought and survived many of the war’s greatest battles; at the Somme in 1916 you were wounded in the leg. When you recovered you returned to fight at the muddier, bloodier Passchendaele in 1917 where you were wounded again.

By 28 September 1918, you are back in action at the Canal de St Quentin. The German infantry are retreating, beaten. Like a wounded tiger they are at their most dangerous. Under heavy fire, you lead a charge on the village of Marcoing and take out a machine-gun post. When you find the bridge ahead is damaged you take planks to repair it and despite more heavy fire you repair the gap, and the advance goes on.

Ahead of you, there are now shattered enemy soldiers staggering away. You can take prisoners, but they are a nuisance – one or more of your comrades will have to escort them back to your lines where they will need more fighting men to guard them. Precious medical resources will be taken from your wounded friends to patch them up. You are bone-weary and wounded again.

It would be easy to let them keep running. But one day soon they will recover enough to regroup and shoot at you. Logic says you shoot the retreating Germans. You are a professional, it’s your job and have survived four charmed years with the medals to prove it. It makes sense to finish what was started four exhausting years ago.

A German corporal about your age comes into your line of fire. What are you going to do? You probably have a round three seconds to decide.

One… you raise your rifle.

Two… you fix him in your sight as he looks you in the eye.

Three… he half raises his hands as your finger tightens on the trigger.

Your time is up. Are you going to shoot him? Yes or no. You have to decide now.

So, what did you decide? Your choice depends on the person you are.

Tandey’s choice was to lower his rifle and nod for the corporal to clear off to safety, which the German did. In 1940 he told a newspaper, “I took aim but couldn’t shoot a wounded man, so I let him go.”

It was a custom of Tandey’s throughout the four years of the war, and it was a situation that happened thousands of times in the Great War. Each of these acts of mercy was usually only significant to the men and their families involved.

But the bullet that Tandey didn’t fire could have been the most important bullet of the twentieth century. The man that Tandey didn’t shoot was corporal Adolf Hitler. If he had pulled the trigger the world may have been spared the far more devastating Second World War.

Henry Tandey was awarded his Victoria Cross in 1919 “for conspicuous bravery at Marcoing on 28 September 1918”. The episode at the end of the battle was forgotten. So much else had happened that day. But he was a hero and would become the most decorated private soldier in the war. His courage was celebrated for another action in which he carried a wounded soldier to safety at the Battle of Ypres. A photo showed Tandey with the wounded man on his back.

And then the myth begins …

The story goes that the newspaper photo was seen by Hitler who recognised the heroic soldier as the man who had spared his life. In 1923 the moment at Ypres depicting Tandey, carrying a fellow soldier to safety was captured in oil-paints by Italian artist Fortunino Matania.

In January 1926, Tandey left the army and took a job at the Standard Motor Car company working in security. Had he been an officer with the VC he could have expected a knighthood. And so he may have carried on to a quiet life and retirement if it hadn’t been for that painting.

A German doctor Otto had fought at Ypres and had treated a British officer Lieutenant-Colonel Earle. They had stayed in touch for 20 years and in 1937 Earle obtained a copy of the painting. He sent it to Dr Schwend as a memento of the battle where they had met. Schwend in turn sent a photo of the painting to Hitler, by then the leader of Germany. Hitler’s secretary wrote back to Schwend to express the Fuhrer’s gratitude.

That would have to wait till 1938 when Hitler was visited by the British prime minister, Neville Chamberlain, who met him at the Eagles Nest retreat in Bavaria in his doomed mission to secure peace. Chamberlain (allegedly) saw the painting and asked Hitler why it was there. The Fuhrer replied, “That’s the man who nearly shot me.” That man the Fuhrer identified as Tandey. Hitler asked Chamberlain to convey his thanks to the man who refrained from pulling the trigger 20 years before.

Chamberlain returned to Britain and stepped off the plane waving a piece of paper and proclaiming, optimistically, “Peace for our time”. However, he did not forget his promise to the Fuhrer that he would phone Tandey and pass on that message. He called Tandey at his home and relayed Hitler’s gratitude.

This would have been the first time Tandey was aware that he had spared the life of the murderous dictator. He later told a reporter, “If only I had known what he would turn out to be. When I saw all the people, women and children he had killed and wounded I was sorry to God I let him go.”

At the time the story attracted little attention. There were more very real problems for the British to face and for the press to report on. It was some years after the war that the incident began to attract attention and focus a spotlight on the unfortunate Henry Tandey.

Tandey’s remarkable legend doesn’t appear in many serious history books because there are inconsistencies. Hitler was on leave in Germany on 28 September 1918 when the battle at Marcoing took place. The two men could have met at Ypres back in 1914 where they both fought. Maybe Hitler misremembered?

Some have suggested that date because he knew Tandey had become one of the most decorated soldiers in the war and a legend that his life was spared by a famous British war hero suited his narrative. We are told that In 1919 Hitler recognised Tandey’s photo at his VC presentation in a British newspaper, but how did he have a copy of a British paper?

In 1937 Hitler saw the painting and apparently wrote a letter of thanks. The letter mentioned that Hitler was moved by the recollections. It said nothing about the central character of Tandey in the image. Chamberlain wrote and kept detailed diaries, but none mention the painting or a phone call to Tandey.

A newspaper article from 1939 says Hitler told Chamberlain the story and Chamberlain told an officer from Tandey’s regiment who then repeated it to Tandey at a reunion in Aug 1939. That was how Tandey found out the story. The phone call from Chamberlain to Tandey at his home did not happen because the phone companies have since said records show Tandey did not have a phone at that time.

However, Tandey is said to have gone to his grave believing the legend that he was the man who spared Hitler. When the Second World War broke out, the 49-year-old Tandey rushed to enlist but because of his Somme wounds he was turned down. He opted to help with the war effort and survived days of Blitz in both Coventry and London, always rueing his failure to shoot the instigator of those attacks.

Henry Tandey died in 1977 at the age of 86 regretting his humanity in those few seconds of the war. His ashes were buried near Marcoing where he had won his VC. He believed that he had cost the lives of millions. True or not he still ought to be remembered as one of the bravest men to have fought in the First World War.

But are such contested stories worth repeating? Maybe. One of the reasons for studying history is to answer the question, “Why do people behave the way they do?” And if history helps you answer that then you may go on to answer the most important question of your life: why you behave the way you do. Who are you?

If you were in Henry’s boots at Ypres would you shoot an unarmed man? Yes, or no?

Knowing what you now know about the identity of the German soldier, would it change your mind about pulling that trigger at Marcoing and shoot him to save seventy million or more? Seventy million, of whom so many were non-combatants killed under the rain of bombs or the horrors of the death camps? Pull the trigger or not?

Yes or no? And you have just three seconds to decide.

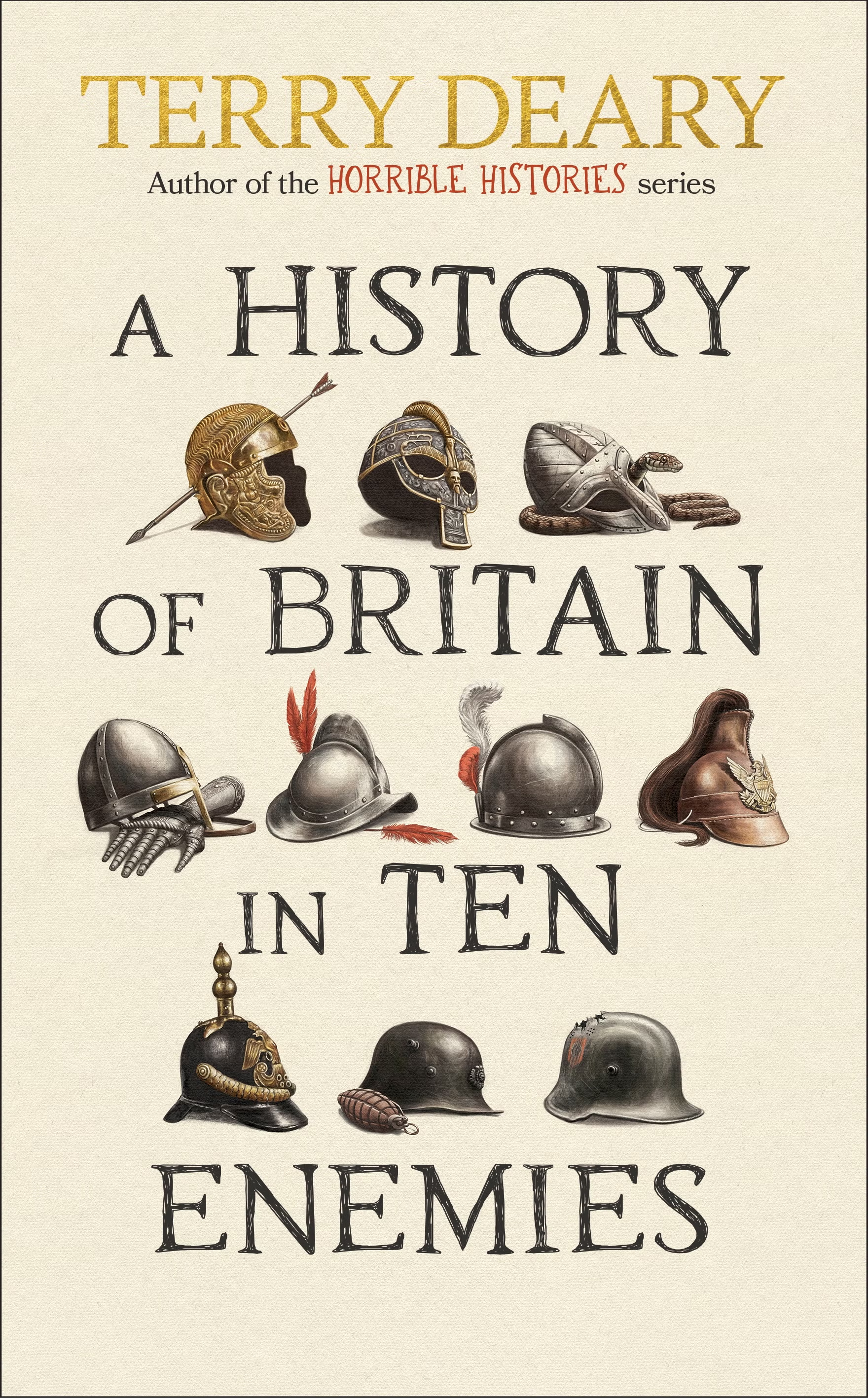

‘A History of Britain in Ten Enemies’ by Terry Deary will be published on October 10 by Bantam

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.