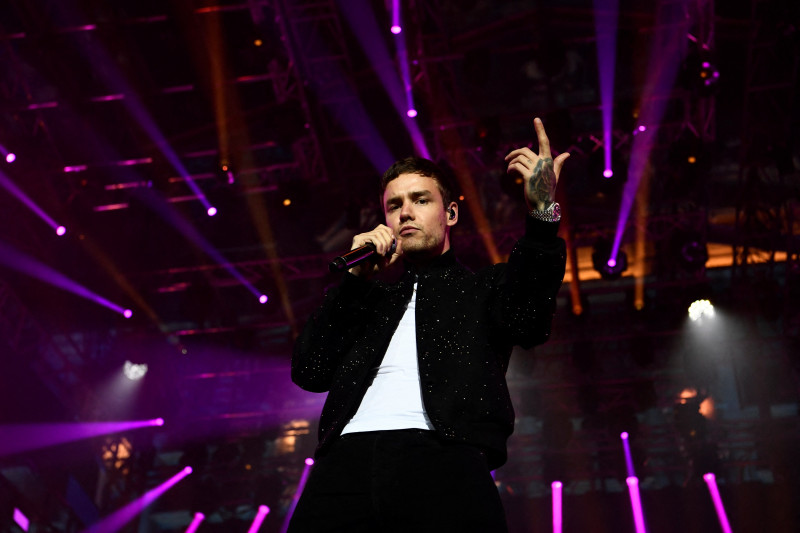

Just a boy. With those three words, Harry Styles’s mother spoke for so many who woke up to the news on Thursday morning that the singer Liam Payne had died. Like her and many others this week, I have felt an overwhelming sadness at the death of this young man, who, at 31 years old, should have had everything to live for. I couldn’t stop thinking about another boy in this story too – his seven-year-old son, Bear – who would have gone to bed as usual that night and woken up without a father. His former partner Cheryl – who herself has spent three years grieving the devastating loss of bandmate Sarah Harding – forced to break the news to him in the morning.

And yet, while details were still emerging about what had happened, the tabloids were already churning out their versions of events, and social media was busy pumping out cruel memes. We know he died after falling from a hotel balcony in Buenos Aires and that he was troubled, navigating a difficult path under the relentless gaze of millions of fans across the globe. We also know he was horribly let down by an industry well-practised in its craft of spitting out its young when they are no longer useful.

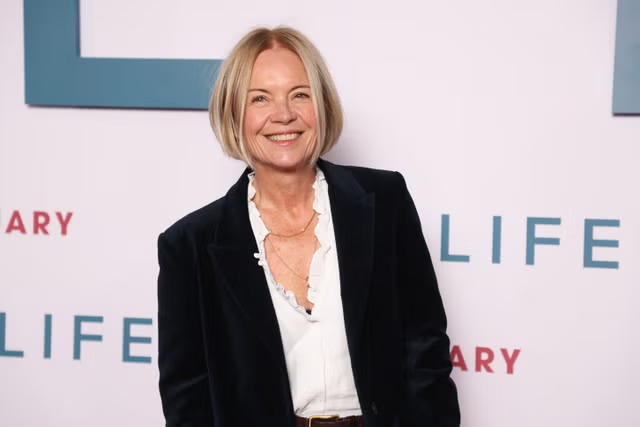

Sharon Osbourne, a former judge on The X Factor, where Payne made his name, alluded to this truth when she reflected: “We all let you down. Where was this industry when you needed them? You were just a kid when you entered one of the toughest industries in the world. Who was in your corner?”

As a showbiz columnist, I interviewed Payne a handful of times backstage at The X Factor and I’ve lost friends in this industry, both behind the scenes and in front of the media spotlight. This latest loss brings me back to a simple question: how many more?

This isn’t even a hidden problem anymore. We now watch young celebrities struggle to cope in plain sight, and instead of offering help, we revel in their demise. Details of their unravelling are traded as fun tittle-tattle. Struggling with being dropped by record labels, falling on hard times – it all makes for a great story.

Until it doesn’t, and you realise there’s a human being at the centre of it all. A human being trying to make sense of their life, but denied the privacy the rest of us take for granted when we do the same.

My first experience of this was when my friend Peaches Geldof died at her country home from an overdose. We had met on the showbiz beat. She called me Showbiz (the name of my column at the magazine I worked was Mr Showbiz), and I called her Peche. We just clicked.

She was 25 when she died, with her two very young children beside her. There had been struggles with drugs and addiction over the years, and despite putting on a brave front, she was fragile, isolated, and struggling to cope. When she died, it hit us hard. I still think about her most days. What would she be doing now?

In 2020, we lost Caroline Flack. Her death sparked a movement online to “be kind”. That it lasted only a hot minute tells you everything you need to know. Carrie and I had started out at the same time; our careers grew, and we would hang out at parties, festivals, and carnival, often sneaking into a corner to gossip and laugh about our wacky lives on the scene.

Her story was complicated. ITV dropped her as the host of Love Island after an incident involving her boyfriend and the police. Losing that job deeply affected her mental health. She loved and hated the world she made a living from; she was obsessed with social media but struggled that her private life had become daily fodder. She needed the attention, but knew how toxic it was.

When she lost her job, there was no real professional support or duty of care. She felt like she was on the scrap heap and would never work again. Her friends and family rallied around her, trying to lift her spirits and convince her things would settle down, but the relentless sensational headlines became too much for her, and she took her own life.

The sadness and anger following her death is something everyone close to her still struggles with. It's why I now help run Flackstock – a festival in her memory that has raised over £500,000 for four charities (Choose Love, Mind, The Samaritans, and the Charlie Waller Trust).

When Caroline died, I had been out of entertainment journalism for seven years. Reality TV was at its peak, and it had turned negative, murky, and dark. Payne, as we know, made his name as a teen on The X Factor – a baby-faced 14-year-old who captured the audience's hearts with his rendition of Sinatra’s “Fly Me to the Moon”.

Deemed too young, Simon Cowell urged him to return two years later, which he did. At 16, he found himself placed in the boy band One Direction after originally auditioning as a solo act. The rest, as they say, is showbiz history. Despite finishing third on the show, One Direction arrived at exactly the right moment to achieve global fame and success.

But, to my mind, shows like The X Factor were toxic; thriving on pitting people against each other and generating spiteful headlines. I had a front-row seat to its nastier elements and it felt to me that contestants (and judges) were regularly used to fuel the tabloid fire. Behind the scenes, at times it was little more than a viper’s nest of gossip, drama, and backstabbing. From the judges to the contestants, even the staff – it felt like a school playground where you had to know the rules.

Here, you weren’t just a contestant on a talent show – you were a puppet. Buckle up, hold on tight, and hope you don’t get thrown off the tracks, kids. Because you weren’t a person anymore – you were a ratings number and a cash cow.

There was so little aftercare on that show in the mid-2000s. Fortunately for One Direction, the boys had a great management team looking after them post-show. But for others they were just there to be rinsed for as much money as possible whenever the chance arose.

One industry insider told me the 1D bubble wasn’t fun at all; a punishing promotional travel schedule turned these boys’ dream jobs into a miserable, exhausting nightmare.

In a 2017 interview, Payne recalled how it was a blur going “from gig to hotel, gig to hotel” – four world tours in five years, plus award ceremonies, recording albums, and churning out merchandise wherever there was money to be made. My friend said the reality was that any “normal touring artist” wouldn’t agree to 10 per cent of what those young boys had to endure.

Of course, from Judy Garland to the Spice Girls, and from Bros to Take That, the early path to fame often turns out to be a rocky road for the young and vulnerable.

As Robbie Williams said in his tribute to Payne this week: “I still had my demons at 31. I relapsed. I was in pain. I was in pain because I relapsed. I relapsed because of a multitude of painful reasons. I remember Heath Ledger passing and thinking, ‘I’m next.’ By the grace of God and/or dumb luck, I’m still here.”

“The internet will, unfortunately, carry on being the internet. The media will, unfortunately, carry on being the media, and fame will carry on being fame.”

It’s tough, but factor in the added pressure of the digital age, and it becomes even tougher. Social media has become the Japanese knotweed of the showbiz industry – you can’t get rid of it. Nasty comments, trolls, fans, negative vibes – it pushes a person’s mental health to the limits, and it’s deeply addictive. Many celebrities I know actively avoid it, having their teams post for them instead.

This gives their brains a break, but it’s also a challenge to keep up with the cultural landscape and stay relevant. Others tread carefully, trying not to read negative comments or engage with toxic content, but even the mentally strongest among them find it hard not to scroll and see what their fans are saying.

Spice Girl Melanie C once told me in no uncertain terms that if social media had existed when the Spice Girls broke into global fame, she might not have made it through the fame circus.

Of course, not everyone becomes a victim. Some manage to balance the delicate deal with the fame devil, giving just enough away while protecting themselves from the worst of it. Somehow, they let the cesspit of social media wash over them. What makes them different? Maybe they have the best people around them. Maybe it’s just luck.

Ultimately, we have to stop thinking of celebrities as otherworldly creatures and stop dehumanising them. No one’s life is on a continual upward trajectory – we all have ups and downs. Taylor Swift has bad days. Ed Sheeran gets in a mood sometimes. Adele isn’t always cackling around town. Beyoncé doesn’t always bounce. They’re just like you and me. They have bad days too.

As Robbie Williams said: “I guess in these moments, it’s worth repeating – we don’t know what’s going on in people’s lives. What pain they’re going through, and what makes them behave the way they do.”

“Before we jump to judgement, a bit of slack needs to be given… even if you don’t really think celebrities or their families exist. They f****** do. Skin and bone and immensely sensitive.”

So, we need to give them a break. We have to allow them to breathe and try and have some time to get themselves back together when things are obviously cracking. It’s heartbreaking to hear the testimony of a young woman staying in the same hotel as Payne saying that he had told her: “I used to be in a boy band – that's why I’m so f**ked up.”

I have shame and regret about how during my years as Mr Showbiz, we treated celebrities’ lives as bloodsports. Amy Winehouse’s addiction spiralling, Jade Goody’s trials and tribulations with Big Brother, Britney Spears shaving her head, the A-list tiny body weight trend in the noughties…the list goes on. They all deserved to be given a break.

We can now just hope that the fame machine starts building in some sort of proper due process so that the young stars can access help when they need it. It takes a special group of people in this industry to properly care and not have pound signs in their eyes when it comes to the talent they look after.

Being in the showbiz world is a bit like being a juicy handsome tuna fish in a shark tank. Everyone is trying to eat you. It gets exhausting swimming around trying to avoid it. But you must keep going.

And we also need to think about our part in this. Sharing that cruel meme on the gram, delighting in some spiteful gossip? The power not to do this is very much in our hands.

The fame machine exists because it needs people to buy into it, but the fragility of life in the celebrity world has never been easier to spot. It’s time to open our eyes. Think before posting. Think before listening. Think before revelling in someone’s failure. Or feasting on the details of their demise.

I think about Caroline often and Peaches too. What a force she would be if she was here today – can you imagine that podcast? It would be exceptional. Her intelligence was enthralling. She didn’t say anything unless she 100 per cent meant it and stood by her statement. I don’t doubt she would have had something great to contribute, but we will never know. Because like her and now Payne – they never stood a chance of growing into the people they could have been

You can read Dean Piper’s substack here

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.