As leader of the opposition, Keir Starmer tended to keep decision-making close, but as prime minister, he may have to consult more widely. He has promised to lead a team at the top of government, although the make-up of the inner ministerial circle is not clear. Journalists have been briefed about a “quad” of top cabinet ministers modelled on the four-person ruling group in the coalition government: Starmer, Rachel Reeves, Angela Rayner and Pat McFadden.

But Starmer has also identified a further four cabinet ministers as “mission leads”, responsible for delivering the government’s missions: Wes Streeting (health), Yvette Cooper (crime and borders), Bridget Phillipson (education) and Ed Miliband (green energy). They will all be allowed four special advisers instead of the usual two each allowed to other cabinet ministers.

Apart from the prime minister, here are the 10 most important people in the new government.

Rachel Reeves, chancellor

She has worked effectively with Starmer in opposition, setting out and sticking to a joint policy of fiscal responsibility. There have been tensions, such as over the slow retreat from the plan to borrow £28bn a year for green investment, but they were managed with decorum on both sides.

One of the aims of the “quad” is to keep the Treasury, the most powerful Whitehall department, aligned with No 10 rather than to allow it to become a rival centre of power.

Angela Rayner, deputy prime minister

Another test of the “quad” structure will be whether it succeeds in binding the leading figure in the Labour government who has a power base independent of the prime minister. Rayner is a street fighter who showed in opposition that she was adept at positioning herself to the left of the leader without open disloyalty, such as on the issue of blocking Diane Abbott as a Labour candidate – on which Rayner, with the mainstream of the party behind her, got her way. As cabinet minister responsible for housing and employment rights, she will work with Reeves to help deliver the “growth” mission.

Pat McFadden, Cabinet Office

The fourth member of the “quad” is the politician who led the election campaign and who has been rewarded with a role at the heart of government holding it all together. He proved his worth to Starmer during the campaign, and will be a trusted enforcer with a brilliant political mind and no ambition of his own. In addition, he is a quietly impressive speaker in the House of Commons.

Sue Gray, chief of staff

She is the most important official in the new government. As a former civil servant, she knows the civil service, but as a political appointment, she will have Starmer’s personal authority behind her. She will work side by side with Elizabeth Perelman, the prime minister’s principal private secretary, but Gray’s political network will be the nervous system of the administration. Her long experience as head of propriety and ethics in the Cabinet Office means that she has a deep understanding of how to handle the tricky problems that so often trip up governments.

Olly Robbins, cabinet secretary?

Simon Case is the current cabinet secretary and head of the civil service, who sat on the prime minister’s right at today’s first meeting of the new cabinet, but he has made it clear that he wants to leave once he has overseen the new government taking its first steps into the world. He is expected to hand over to Robbins, a career civil servant who was Theresa May’s Brexit negotiator and who is a firm ally of Gray’s. The other civil servant who will be significant in the new government is James Bowler, the permanent secretary at the Treasury, another ally of Gray’s.

Morgan McSweeney, political secretary?

The self-effacing Labour apparatchik who ran Starmer’s leadership campaign – and then the general election campaign on a very different prospectus – was once said to be intending to step aside once his work of taking Labour back to power was done. But it seems likely that he will continue to play a role in No 10. Whether he is given the formal title of political secretary or not, his role will be to keep the prime minister connected to the party, and to stay focused on the next election.

Matthew Doyle, Starmer’s spokesperson

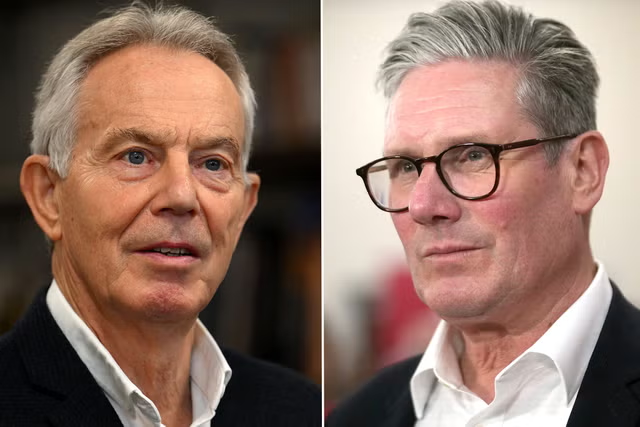

The Alastair Campbell of the new government. As a junior press officer in No 10 when Tony Blair was prime minister, he worked with Campbell, so he knows not to repeat Campbell’s mistake of “becoming the story”. He will work in partnership with David Pares, the civil servant who is currently the prime minister’s official spokesperson, but it is to Doyle that journalists will turn for briefings about “what Keir thinks”.

Deborah Mattinson, director of strategy

She is another experienced operator, having worked on opinion polling and focus groups for the party since the 1980s. She worked for Gordon Brown but fell out with him, and wrote a book about the experience called Talking to a Brick Wall, which was ostensibly about voters’ feelings of being ignored by politicians. She is the driving force behind Starmer’s appeal to what she calls “hero voters” – working-class Labour supporters who switched to Boris Johnson but who were won back this time. Her job will be to ensure that the Labour government delivers for them.

Peter Hyman, senior adviser

Another adviser from the New Labour era. He worked for Tony Blair in opposition and in government, one of many credited with the success of Labour’s pledge card in the 1997 election. He spent a long time out of politics, teaching and founding a school, but came back to work for Starmer. He and Mattinson crafted the five “missions” intended to maintain message discipline during the election campaign, but also to ensure focus on delivery in government.

Alan Campbell, chief whip

He sits on the front bench in parliament, a few seats away from Starmer, and yet remains almost completely unknown to the general public. His role will be critical in the new government because it is his job to know what all 411 Labour MPs are thinking – and sensing when rebellion is brewing. Two of his early challenges will be managing pressure from new MPs to lift the two-child limit on benefits, and to adopt a more pro-Palestinian line on Gaza. But because his advice to the prime minister is critical to MPs’ chances of promotion, he has the power to keep the troops in line.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.