Within hours of Hamas’s dawn attack a year ago, British Jews were consumed by horror and grief, shadowed by sudden overwhelming fear for their own safety. The first hint of what was to come was the crowds that started to gather on London’s Edgware Road. While Hamas was still hunting Jews in southern Israel and the first terrifying details were emerging about the bloody and torturous scenes that saw 1,200 people losing their lives and 251 hostages taken, motorists were seen honking their horns and waving Palestinian flags in delight at the deadliest day of Jew slaughter since the Holocaust.

If the residents of Golders Green, in the heart of Jewish north London, had any doubt that the atrocities in southern Israel would echo in their own lives, their fears were confirmed by Monday morning when they awoke to see “Palestine will be free” scrawled 30 ft-wide across Golders Green Road railway bridge.

Later that day, 2,000 people gathered outside the Israeli embassy in central London; whooping and setting off fireworks they cried out for a “global intifada”. Daniel*, a Jewish Londoner in his twenties remembers being shocked at how quickly people felt emboldened to say the most heinous things. “People saying Jews deserve to be killed and kidnapped, that Israel staged 7 October! It was scary how people said these evil things without shame or consequence.”

It was already clear that, for an alarming number of British citizens, the denial of Israel’s right to exist justified the targeting of every Jew, whether they lived in Tel Aviv or Tottenham.

In the weeks that followed, Jewish schools, including two in Stamford Hill in north London, were daubed with red paint. Some schools conducted “invacuation” drills, with pupils practising taking shelter in safe areas in case of a threat.

Sarah Miller from Bushey, whose two children both attend Jewish schools, says in the days after 7 October, both her children became acutely aware of what antisemitism is.

“My daughter, who is now 14, was told to take off her uniform when going to and from school, while my son, now 10, experienced anti-Jewish jibes on a computer games platform from other users.

“We largely shielded him from the true horror of what happened that day, but he knew there had been an attack and that children had been kidnapped. He would ask us ‘Is a bad man going to come through the window and get me?’”

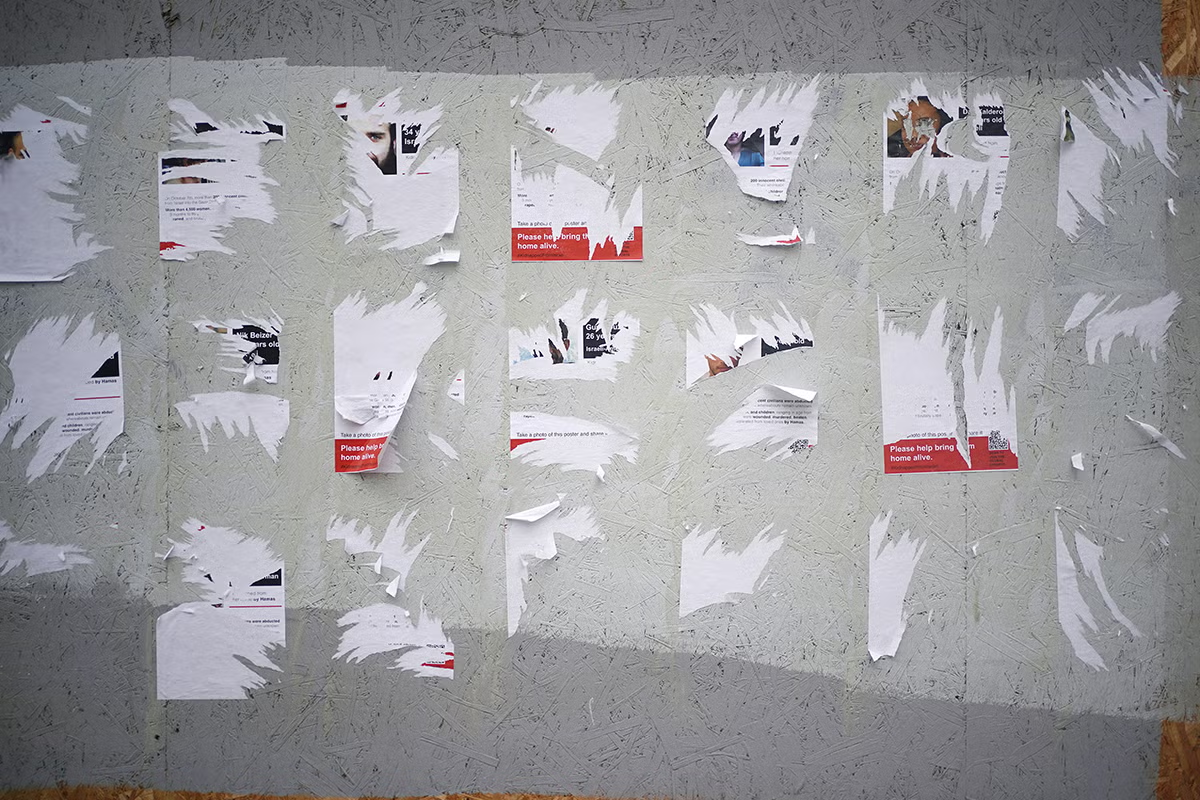

In a show of sympathy and solidarity for the families of the hostages, posters were carefully put up on lamp posts and at bus stops in Jewish neighbourhoods. But in the most chilling example of atavistic antisemitism, within hours they were defaced and torn down. On my high street, one featuring Kfir Bibas, a baby and the youngest hostage, who remains in captivity, was defaced with the word “Nazi” scrawled across his face.

Sara remembers: “My children couldn’t understand why people would want to tear them down. Or why there is so much hatred in the world and those who would do harm to us just because we are Jewish in this country where my family has been for four generations.”

The fear of attack spread quickly. “The atmosphere in London feels very tense,” says Rivka (not her real name), a dual British-Israeli woman who lives in Tottenham. “I put up posters of kidnapped Israelis, but a group of teenage girls shouted ‘Free Palestine!’ and waited for me to walk away, then tore them down while smiling at me. A year on and I am constantly on edge when I walk on the streets or take public transport.”

Data published last week by the Community Security Trust (CST), which monitors antisemitism in the UK, reported that attacks on British Jews tripled between 7 October 2023 and 30 September 2024, with 5,583 incidents – the highest of any 12-month period since 1984. Most incidents involved abusive behaviour, property damage and desecration.

In total, there were 1,978 incidents recorded, with 122 cases involving extreme violence and assault. Almost half of these incidents occurred in just four boroughs: Barnet and Hackney in Greater London and Bury and Salford in Greater Manchester, where the four largest Jewish communities are located.

Of particular concern has been the rise in child-on-child antisemitic violence, indicating that intolerance is taking root at an increasingly young age. A swastika was daubed in the toilets of a private girls’ school in London and Jewish year 7 pupils were assaulted at Belsize Park Underground station by children from another school.

The mother of one of the students says: “They ran ahead of my son and kicked one of his friends to the ground. They were trying to push another kid towards the tracks. They got him as far as the yellow line and threw his kippah onto the tracks.

“My son ran a few steps up to try and get help. They ran after him, he was elbowed in the cheek and hit his head against the wall. They dislodged a tooth and shouted, ‘Get out of the city, Jew!’”

In response to this growing threat, many Jews I know have reluctantly removed the mezuzah from their front door, the small case containing a verse from the Torah traditionally attached to Jewish homes. Friends routinely tuck their star of David necklaces inside their clothes, wear hats over their skullcaps and hesitate to wear yellow bracelets and ribbon badges to show solidarity with the hostages who are still being held in Gaza.

Hamas took delight in filming their massacre, even using their victims’ phones and uploading it onto their victims’ social media for their friends and family to witness. Yet so many of my fellow students deny what they can see with their own eyes

For the first time in 80 years, European Jews fear being identified in public, but British Jews were, of course, not blind to the scourge of antisemitism before 7 October. They were, however, entirely unprepared for its magnitude. As one rabbi put it: “It was like a light had been switched on. Suddenly we saw what had always been there.”

In January, Nicola Richards, the former MP for West Bromwich East, gave a flavour of what Jewish people across England were facing: In Bristol, “Free Palestine” was shouted at visibly Jewish men walking to a Sabbath lunch. In Leeds, a Jewish university footballer was called a “big nose Jew” by a member of the opposing team. In Manchester, a Jewish school was sent a letter saying “Warning, your school is being targeted, no one is safe, no one should support killers, Palestine forever.”

She continued: “In London, The Wiener Holocaust Library, named after Lord Finkelstein’s grandfather, who escaped the Nazis, had ‘Gaza’ spray-painted on its sign. In my area of the West Midlands, a swastika was painted on a bridge, and a curry house announced its full support of Hamas. I thank West Midlands police for its support over the last few days in dealing with localised incidents incredibly fast.”

Jewish students also report being harassed on university campuses. Seven out of 10 Jewish students say they are now “uncomfortable” revealing their Jewish identity on campus, according to a poll published last week by the Intra-Communal Professorial Group.

Daniel (not his real name), a second-year student at the University of Leeds, where protesters graffitied a building for Jewish students, says: “I never understood how people can deny the Holocaust. Now I get it.

“Hamas took delight in filming their massacre, even using their victims’ phones and uploading it onto their victims’ social media for their friends and family to witness. Yet so many of my fellow students deny what they can see with their own eyes. I sit in lecture halls with students who laugh in my face when I tell them I’m worried about my family and friends in Israel.”

Phil Rosenberg was elected president of the Board of Deputies of British Jews this summer. At 38, he is the youngest leader in its more than 260-year history – tasked with guiding his community through its gravest challenge since the Second World War.

I put up posters of kidnapped Israelis, but a group of teenage girls shouted ‘Free Palestine!’ and waited for me to walk away, then tore them down while smiling at me

He says: “The attacks of 7 October have inflicted deep trauma. Many British Jews have friends and family who were murdered and kidnapped. A family friend, Nathaniel Young, aged 20, was killed in the initial attack and one of my staff has a cousin, Tsachi Idan, who is still being held hostage in Gaza after his oldest daughter was shot and killed through their safe room door.

“I’ve set out five priorities to stand up for British Jews: fight antisemitism, campaign for peace and security in Israel and the Middle East, defend our religious freedoms, make our community more united and inclusive and celebrate our identity as British Jews. I also plan to launch a commission on antisemitism to tackle this hatred at its roots.”

Rosenberg, who recently brought together 60 Jewish and Muslim leaders in an attempt to revive interfaith dialogue, is not the only community leader taking unprecedented steps to reverse the tide of hatred.

The Jewish Leadership Council (JLC) has launched a strategy called Forge the Future to address what its chair, Keith Black, describes as “the fight of our lives”. This plan calls for a more decisive governmental response to antisemitic attacks, increased security measures, support for young Jews in schools and universities and strengthening ties with wider society.

JLC chief executive Claudia Mendoza says: “While we cannot return to ‘normal life’ as it was before 7 October, we are prepared to take whatever steps are necessary to meet the changing needs of our community. We do not underestimate the challenges, but we want to work across the community and beyond to deal with these challenges head on.”

Mendoza adds: “We know the threat of extremism challenges everyone in society, not just Jews. We must all unite against it.”

He says that seeing the word “Zionist” – which describes anyone who supports a two-state solution – being turned into a pejorative has been excruciating for British Jews, 70 per cent of whom have family in Israel. While some Jewish people have joined in the pro-Palestinan marches which are regularly held to call for a ceasefire and protest at the tens of thousands of lives that have been lost in Gaza this year, banners declaring “Zionism = racism” are also commonplace. As are placards comparing Israel to Nazi Germany, or claiming Zionists control the British government and media

Dave Rich, the CST’s director of policy, says: “The increase in anti-Jewish hatred in this country ought to have shaken any complacency about the presence and scale of antisemitism in our society. It has appeared everywhere – on our streets, in schools, universities, hospitals, workplaces and online. A lot of British Jews have been left wondering where this ends and why too few voices have spoken out against it.”

But amid the hostility, there have been moments of hope. Jewish communities nationwide have come together, organising fundraisers and aid packages for families of hostages. The Hertfordshire Jewish Forum has held 50 weekly vigils, attended by MPs and survivors of the 7 October attack and three major rallies have taken place.

In November, 100,000 people participated in a United Against Antisemitism march in central London, described as “the largest demonstration of its kind since the Battle of Cable Street”. In January and June, the Hostages and Missing Families Forum UK and the 7/10 Human Chain Project held gatherings in Trafalgar Square, united by the plea: “Bring them home now.”

With poignant timing, the first anniversary of the Hamas attack comes just days after Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish new year festival of reflection and renewal.

Everyone attending synagogue in recent days will have reflected on the uncertain future facing their family and community in a country that, at times, has never felt so alien and altered.

As Board of Deputies president Rosenberg puts it: “As we mark one year since 7 October, I pray this can be the beginning of a journey from death and destruction, from division and despair to a place of empathy, hope and, most importantly, peace.”

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.