Your support helps us to tell the story

Support NowThis election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

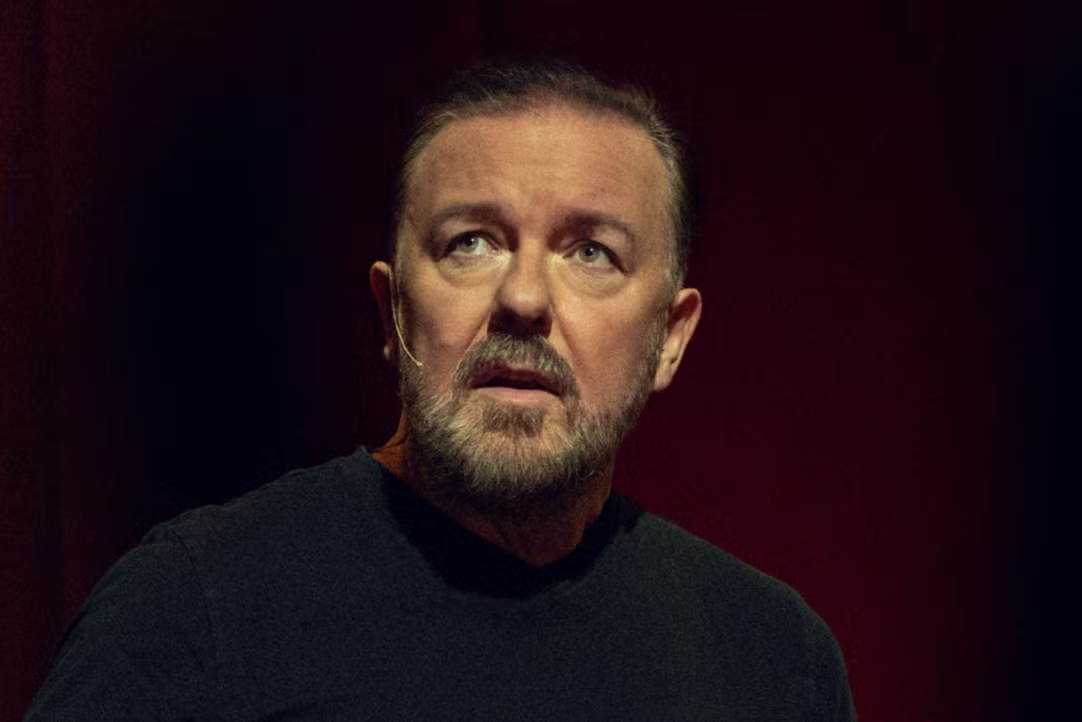

Here’s a hypothetical for you. What would a Ricky Gervais stand-up set look like if he had existed before the internet?

Few comedians have been altered so drastically by the sickly mirror of social media than Gervais, the man who was once comedy’s great televisual innovator. What makes Gervais such a curious case is that little of his work feels particularly modern: there is nothing really about any of his TV projects – brilliantly biting The Office and Extras; mawkish care home dramedy Derek; Warwick Davis-fronted cringe sitcom Life’s Too Short; award-winning grief comedy After Life – that really situates it in the era of Twitter feeds and Instagram filters.

His stand-up comedy, too – which has rematerialised this week, with the launch of a new UK tour – is, in its choice of material, almost doggedly atavistic. If you go to a Ricky Gervais show, you will invariably see him fixate on age-old subjects such as religion, science, or philosophy. His frames of reference would not be so very out of place half a century ago. And yet, Gervais’s recent work (particularly his stand-up sets, which he tours widely before releasing filmed versions on Netflix) is utterly immersed in the discourse churn of the Twittersphere. His routines now devote considerable energy towards ridiculing those (online) dissenters who have called him out for ableism, or transphobic comedy, and goading them with more of the same.

In a review of Gervais’s new tour show, the Telegraph wrote that Gervais seems “like a man who used to be the funniest bloke in the pub delivering material written after spending too much time online”. It’s a damning assessment, perhaps because it feels so plainly true. As anyone with Twitter/X will probably know, Gervais is a prolific user of Elon Musk’s social media platform. Twitter/X is his biggest champion and his battleground. When the so-called woke brigade comes at him with pitchforks and “cancellation”, angered by one of his many knowingly poor-taste stand-up jokes about minorities, it is on social media that they do it. Gervais uses the platform to relentlessly share affirmations of his own work, dispatch snide deflations unto his critics, and, seemingly, mine any backlash for future material. The idea of Gervais as a kind of obstinate sceptic-provocateur is now the heart of his own branding. But he’s in no way any funnier because of this.

Gervais seems unable, or unwilling, to apply the same scepticism he wields against, say, organised religion, to the contradictions of his own rhetoric. He has noted that the many criticisms of his jokes – his use of ableist slurs, his routines targeting trans people – have done nothing to stymie his popularity. After Life was, as he has repeatedly mentioned on Twitter/X, a huge hit and unequivocal commercial success. This new tour, Mortality, will run into next summer, and includes arena dates and a US leg, with performances at the Hollywood Bowl and New York’s Radio City Music Hall.

He is, in other words, doing more than OK. Surely, this very fact ought to suggest that criticisms of his work are inert. He has not been cancelled. Not even close. What value, then, is there in moulding his entire persona around opposition to a force that has no material power? By aiming his munitions at a nebulous enemy – online backlash, the quote-unquote woke mob – he is waging a battle that can never be won or lost. So he is free to keep shooting, again and again and again.

It’s a shame, because Gervais’s best work is of such bald truth and creative cunning that no one can doubt he has better arguments to make. And I don’t just mean The Office. His early specials Animals (2003) and Politics (2004) were effusively received, and proved he was able to translate his TV stardom into something real and substantial on stage. Above, I described his stand-up’s preoccupations as atavistic, but this often worked in his favour. In the 2000s, when the default mode of British popular stand-up was banal observation – “Have you ever noticed how there’s a drawer in your house full of wires and bits of string? Ha ha ha” – Gervais was unafraid to tackle big subjects, big ideas.

The Mortality tour, as you may gather by its title, seems like an attempt to keel back to this ethos. But he needs to lose the rest of it – the persecution complex, the self-conscious mission to offend the offendable. Gervais should, in other words, just log off.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.