When it comes to our brains, neuroscientists have found that sex and gender are associated with distinct neural networks; and researchers hope that their findings will underscore the importance of considering sex and gender separately in medical contexts to ensure equal access to optimal treatment outcomes.

According to the National Institutes of Health, sex is a biological construct assigned at birth based on physical attributes like our anatomy and X and Y chromosomes. Gender, meanwhile, refers to a multidimensional construct based on identity as well as social and cultural expectations.

Increasingly, studies have pointed toward clear neurological differences between the male and female brain. But whether these differences are driven by biological or social factors has largely been a mystery.

"Sex and gender are distinct from one another, and both are associated with biological, social, and environmental factors," Elvisha Dhamala, an assistant professor of psychiatry at the Feinstein Institutes of Medical Research and the Zucker Hillside Hospital in Glen Oaks, New York, told Newsweek.

"Unfortunately, in biomedical research, the two have often been conflated or equated with one another.

"While interactions between sex and the brain have been studied, we have a limited understanding of how gender maps onto the brain. An understanding of how sex and gender independently and collectively influence the brain is critical as this can inform future work on brain disorders with known sex and gender differences in prevalence."

In a new study, published in the journal Science Advances, Dhamala and colleagues set about untangling the influences of sex and gender on our brains.

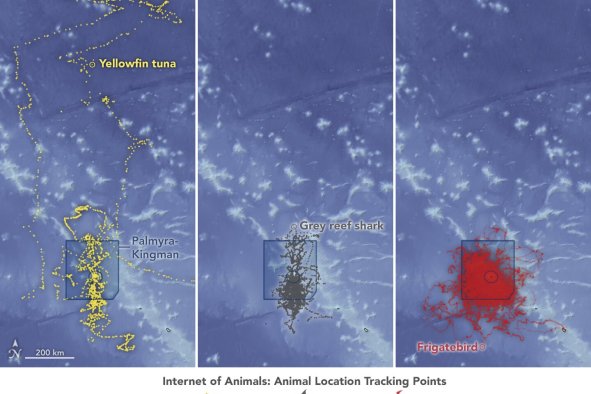

"In this study, we explored how sex and gender affect brain networks, which describe how different parts of the brain are active and connected," Dhamala said. "Using data from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study with 4,757 participants, we analyzed functional MRI data to see how different brain regions communicate and form networks."

The team explored how these networks related to the individuals' binary assignment of sex at birth and to their gender, as reported by the young participants and their parents. "We found that sex and gender each influence different brain networks," Dhamala said.

"This means we need to consider sex and gender separately in future brain studies. It's crucial to distinguish between sex and gender when collecting, analyzing, and interpreting data."

In particular, networks involved in motor control, vision, emotions and behavior were more strongly associated with sex, while networks associated with gender were largely distributed through brain regions involved in learning, memory, reasoning and consciousness.

In this study, the researchers only considered these relationships between brain networks, sex, and gender in youth at single time point, so were not able to comment on how these relationships might change throughout the course of development and into adulthood. However, they do plan to build upon this work and study these relationships throughout the life span.

"This work demonstrates that gender has an independent influence on the brain, beyond the influence of sex itself, and these influences map onto distinct functional brain networks," Dhamala said. "Moving forward, this tells us that we need to consider sex and gender separately if we want to better understand the brain"

Because this data was collected at a single timepoint during adolescence, it is unclear how these relationships may evolve as we grow into adulthood. The team plan to follow up their findings with further studies into the relationships between sex and gender and brain networks throughout the life span.

"The future of biomedical research hinges on us considering sex and gender separately if we want improved health outcomes for all," Dhamala said.

Is there a health problem that's worrying you? Let us know via health@newsweek.com. We can ask experts for advice, and your story could be featured on Newsweek.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.