Scientists have revealed two never-before-seen groups of microbes that live in the hot springs of Yellowstone National Park.

Researchers from Montana State University made the discovery, published in the journal Nature, that may have implications for the search for extraterrestrial life and the fight against climate change.

The team reported that the new microbe groups, dubbed Methanomethylicia and Methanodesulfokora, are methanogens, single-celled organisms that produce methane.

While humans and other animals eat food, inhale oxygen and exhale carbon dioxide to survive, methanogens eat molecules like carbon dioxide and breathe out methane and often cannot survive in the presence of oxygen.

Scientists long believed that all methane-producing microbes belonged to one single group amid the tree of life, a phylum called Euryarchaeota. However, the revelation of the two new microbial groups, previously only known from DNA samples, confirms that methane-producing microbes are more diverse than thought.

"All we knew about these organisms was their DNA," microbiologist Roland Hatzenpichler of Montana State, an author of the paper, said in a statement.

"No one had ever seen a cell of these supposed methanogens; no one knew if they actually used their methanogenesis genes, or if they were growing by some other means."

While Methanodesulfokora is found mainly in hydrothermal springs and deep-sea vents, Methanomethylicia is more widespread, appearing in wastewater treatment plants, animal guts, and other environments like marine sediments and wetlands.

This is significant as methanogens produce 70 percent of the world's methane—a gas 28 times more potent than carbon dioxide when it comes to trapping heat in the atmosphere, Hatzenpichler said.

"Methane levels are increasing at a much higher rate than carbon dioxide, and humans are pumping methane at a higher rate into the atmosphere than ever before," he added.

Researchers still need to determine if Methanomethylicia in non-extreme environments uses methanogenesis to grow or if they rely on other methods. Understanding this could help scientists learn how to alter conditions in the environments where they are found so that less methane is emitted into the atmosphere.

"My best bet is that they sometimes grow by making methane, and sometimes they do something else entirely, but we don't know when they grow, or how, or why. We now need to find out when they contribute to methane cycling and when not," Hatzenpichler said.

NASA's exobiology program also funded the research, as it is interested in methanogens because they may give insights into life on Earth more than 3 billion years ago and the potential for life on other planets and moons where methane has been detected.

According to Hatzenpichler, it was "painstaking work" to harvest the samples from Yellowstone National Park, which recently experienced an explosion from one of its boiling geysers in an area called the Biscuit Basin.

In the study, the team extracted the microbes from sediment samples from Yellowstone's hot springs, which range in temperature from 141 to 161 degrees Fahrenheit.

Cultivating the microbes in the lab, the research team demonstrated that these organisms not only survived but thrived—and released methane in the process.

"Until our studies, no experimental work had been done on these microbes, aside from DNA sequencing," Hatzenpichler said.

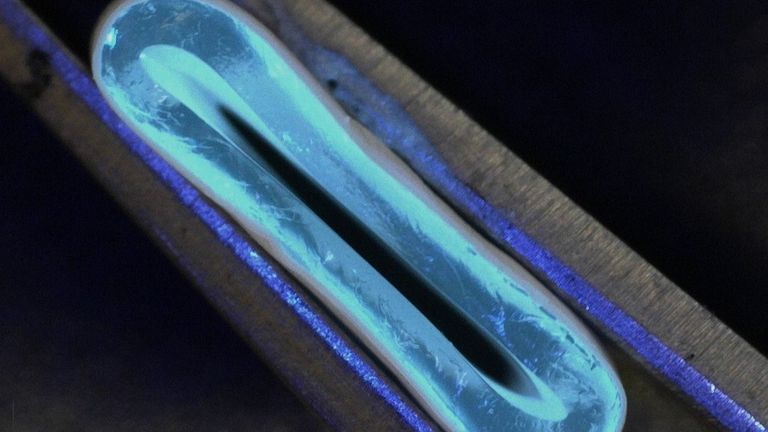

The team also found a unique feature in Methanomethylicia: the microbes form previously unknown cell-to-cell tubes linking two or three of them together.

"We have no idea why they are forming them. Structures like these have rarely been seen in microbes," Hatzenpichler said.

"Maybe they exchange DNA; maybe they exchange chemicals. We don't know yet."

Do you have a tip on a science story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about Yellowstone or methane? Let us know via science@newsweek.com.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.