Exposure to agricultural pesticides could be as bad as tobacco smoke for increasing our risk of certain cancers, a study has found. However, while these findings are thought-provoking, some experts have described the findings as misleading.

In the U.S., roughly 1 billion pounds of conventional pesticides are used every year to control weeds, insects and other pests, the United States Geological Survey reports. These chemicals can linger on our fruit and vegetables and seep into our waterways, meaning that many of us are ingesting them in small quantities on a regular basis.

The health impacts of these chemicals depends on the type of pesticide. Some, like the legacy pesticides organophosphates and carbamates, have been associated with neurological disorders and hormonal disruptions. Others have been flagged for their potential to increase our risk of cancer.

"The evidence linking some cancers with some pesticides is growing, particularly for those who regularly directly work with them," said Terry Slevin, CEO of the Public Health Association of Australia, in a statement. "Establishing the precise nature of that connection is scientifically challenging so there remains debate.

"[Having said that,] for some pesticides there is strong evidence of cancer link (Lindane and non-Hodgkins lymphoma being an example)," said Slevin, an honorary professor at the Australian National University and adjunct professor at the National Drug Research Institute at Australia's Curtin University.

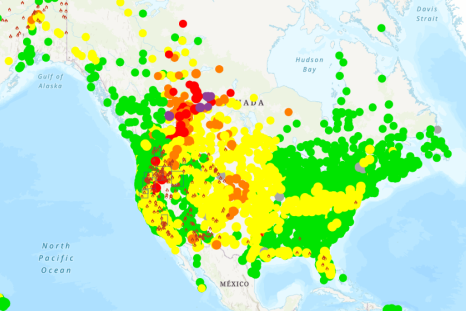

In a new study, published in the journal Frontiers in Cancer Control and Society, researchers from Colorado's Rocky Vista University used nationwide population data to evaluate the association between pesticide exposure and the risk of developing various cancers.

The researchers looked at 69 different pesticides in their analysis, arguing that, in the real world, people are unlikely to be exposed to a single pesticide but rather a "cocktail" of different chemicals, specific to the land use in their region.

After accounting for other potentially confounding variables, like smoking rates and socioeconomic status, the researchers found that living in communities with heavy agricultural production and pesticide exposure was associated with the development of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, leukemia and cancers of the bladder, colon, lung and pancreas.

"Our study showed the strongest association between certain patterns of pesticide use and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma," the researchers write. "The effects of pesticides on these cancer types were more significant than the effects of smoking."

However, scientists who were not involved in this research have described these comparisons as misleading.

"The assertion that living in an environment heavily exposed to pesticides could increase the incidence of cancer as much as smoking is misleading because lung cancer is not the basis of the observation," Bernard Stewart, a professor in pediatrics at the University of New South Wales, said in a statement.

"That the observation applies only to Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma, leukemia and bladder cancer largely invalidates the assertion because smoking does not cause Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma or leukemia apart from the acute myeloid type," he said.

Slevin said that it was "a step-too-far from this level of analysis to suggest that the burden is comparable to tobacco, which causes more than 8 million deaths worldwide each year."

Experts have also raised concerns about the methods used to reach these findings.

"This paper attempts to identify cancer risks due to pesticide use by examining cancer rates in U.S. counties with their rates of pesticide usage," said Ian Musgrave, a senior lecturer in medicine at Australia's University of Adelaide, in a statement. "This provides an association but does not provide evidence of causation.

"The major issue is that there is no real quantitation of exposure, and it is assumed that the local usage level in agriculture equates to exposure to all people in that county," he said.

Oliver Jones, a professor of chemistry at Australia's RMIT University, said that while the results were "thought-provoking," the research was not without its limitations and "should not be a cause for panic."

Do you have a tip on a health story that Newsweek should be covering? Let us know via science@newsweek.com.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.