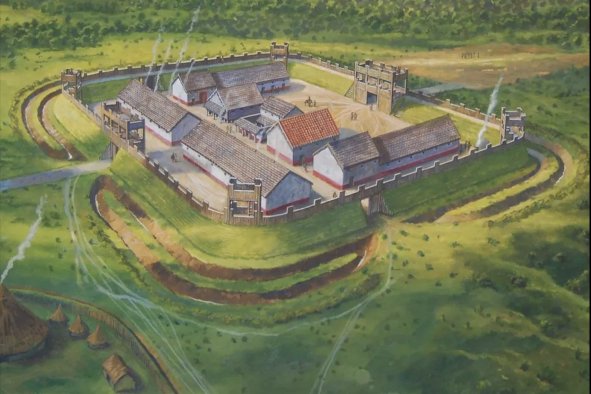

Archaeologists have uncovered a prehistoric settlement dated to around 7,000 years ago that was inhabited by early European farmers.

The settlement was identified by a team from the Archaeological Institute of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, near Kutná Hora, a town in the Central Bohemian region of the country.

The discovery sheds light on the lives of early European farming communities during the Neolithic period, sometimes referred to as the New Stone Age.

"The find shows us how the settlements of the older Neolithic in Central Europe looked and functioned. Although many similar settlements are known, this one is very well preserved ... and at the same time we can perform modern analyses on it, which will provide a lot of unique data," institute archaeologist Daniel Pilař told Newsweek.

The good state of preservation of the settlement can be explained by the fortuitous fact that no other settlements were built on the site over the course of the following millennia.

The remains of the settlement were initially found due to building activity, according to Pilař. During construction of a barn, after the topsoil was removed, the ground plans of long houses—typical dwellings of the time—and large pits full of prehistoric pottery were revealed.

"Thus, after the first day of excavation we already knew that we had found a new Neolithic settlement," Pilař said.

While the long houses themselves have not survived, the researchers found pits in the ground that demarcate the layout of the structures.

"Regarding the use of houses, it must be noted that until recently, most daily activities took place outside the house and people moved inside because of the cold or rain. In the summer, most activities took place outside, from food preparation to crafts. Not least because it was simply dark in the houses," Pilař said in a news release.

In winter, on the other hand, the houses provided good shelter from the cold and rain. During these months, people engaged in some crafts inside their homes.

It is impossible to say exactly how many people at any one time lived in the settlement, which was on a plain between two streams, but the number may have been in the low teens, according to Pilař.

The Neolithic inhabitants of the settlement cultivated plants and raised cattle to provide food for themselves, but they also engaged in hunting and gathering activities.

"Interestingly, this settlement was located on the very edge of an area that was suitable for prehistoric agriculture," Pilař told Newsweek.

The people who settled at the site represented some of the first farmers in what is now the territory of the Czech Republic. They arrived from the Balkans region of southeastern Europe and gradually populated the area.

"We call these earliest Neolithic communities in the area the 'Linear Pottery Culture.' By this we mean communities that had, for example, similar pottery, settlements or burial practices. But we don't know anything about their language or identity. Therefore, we cannot associate these prehistoric societies with any ethnic/cultural group that we know from younger periods," Pilař said.

In addition to the remnants of the long houses, the surrounding pits filled with pottery were also an important find. These pits were used to mine clay and subsequently filled with waste. This material is now providing a window into the daily life of the settlement.

Most of the finds in the pits consist of ceramics—these objects were used for cooking, serving and storage. But archaeologists also uncovered tools, such as flint blades, sharpened axes and stone grinders—inside.

Do you have a tip on a science story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about archaeology? Let us know via science@newsweek.com.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.