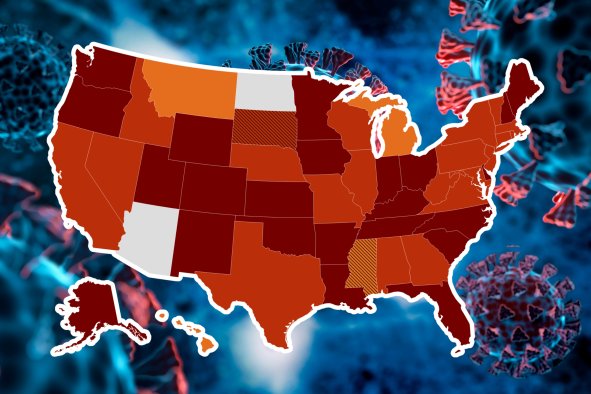

COVID lockdowns may have caused teenagers' brains to age prematurely, research suggests. This accelerated maturation was particularly pronounced in young girls, with potentially irreversible structural changes seen in all areas of their brains.

The restrictive measures introduced between 2020 and 2021 played an important role in curbing the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus. However, these lockdowns came at a cost: the disruption of daily routines and social activities. These disruptions are thought to have been particularly harmful to teenagers, who rely on social interactions to develop their sense of self-identity and control.

"We think of the COVID-19 pandemic as a health crisis, but we know that it produced other profound changes in our lives, especially for teenagers," said Patricia Kuhl, senior author of the new study and co-director of the University of Washington's Institute for Learning & Brain Sciences (I-LABS), in a statement.

In 2018, Kuhl and her colleagues at the University of Washington embarked on a longitudinal study with 160 teenagers between the ages of 9 and 17 to evaluate the changes in brain structure during typical adolescence. In particular, the team set out to explore changes in the outer layer of the brain called the cerebral cortex, which is known to get thinner as we age.

However, in 2020 it became clear that the teenage experiences of these participants would be far from "normal."

"Once the pandemic was underway, we started to think about which brain measures would allow us to estimate what the pandemic lockdown had done to the brain," Neva Corrigan, lead author of the study and a research scientist at I-LABS, said in a statement. "What did it mean for our teens to be at home rather than in their social groups—not at school, not playing sports, not hanging out?"

Chronic stress and negative life events are known to accelerate cortical thinning, which is linked to an increased risk of developing mental health disorders, particularly among young women. So what effects might a global pandemic have on these changes in brain structure?

Using its original data from 2018, the team created a model to show the expected trajectory of cortical thinning for these teenagers. The participants were then brought in for a second brain scan in 2021 to compare how their brains had actually changed during this period.

On average, the teens' brains showed significantly accelerated cortical thinning, with particularly pronounced effects in females. While boys showed cortical thinning only in the visual cortex, girls showed thinning all over their brains.

The researchers believe that this gender disparity may be due to differences in how girls and boys tend to socialize and the societal stresses they may feel because of social media.

"Teenagers really are walking a tightrope, trying to get their lives together," Kuhl said. "They're under tremendous pressure. Then a global pandemic strikes, and their normal channels of stress release are gone. Those release outlets aren't there anymore, but the social criticisms and pressures remain because of social media.

"What the pandemic really seems to have done is to isolate girls," she said. "All teenagers got isolated, but girls suffered more. It affected their brains much more dramatically."

Kuhl said that while it is possible these teenagers might see some recovery, such as slower thinning over time, the cerebral cortex is unlikely to get thicker again.

However, this study does have some major flaws. To start, while global lockdowns were associated with brain thinning for these teenagers, many other variables occurred during this period that may have contributed to these brain changes too.

"The study shows that post lockdown female brains overall demonstrated greater than expected cortical thinning but not that the lockdown measures actually caused the thinning," said Rebecca Sheriff, a consultant psychiatrist and senior clinical research fellow at the University of Oxford, in a statement.

She said the study excluded a rather large proportion of young people because of their mental health history.

"Participants were excluded if they had ever been diagnosed with a developmental or psychiatric disorder, which, given that up to one in five adolescents have a probable mental disorder, seems quite an omission. In addition, it does not report on other sources of stress so we can't tell if there are other possible reasons for the brain changes," Sheriff said.

According to Richard Bethlehem, an assistant professor of neuroinformatics at the University of Cambridge, it is difficult to apply these findings to the general population.

"Firstly, the samples are quite small, so we need to be cautious not to generalise these findings to all adolescents," he said in a statement.

"Secondly, there is not a huge amount of information about these samples beyond the fact that they were collected at different times during the pandemic so we cannot assume it definitely is the lockdown which is the cause of these reported changes in the brain.

"For example, many other things may have happened during the pandemic period such as infection with covid or a number of infections. There are many factors that are not modelled or documented in this paper which could potentially explain these findings beyond the lockdowns themselves," Bethlehem said.

Clearly, more work is needed to confirm whether lockdowns themselves were directly responsible for these effects, but the study adds to our understanding of the fragility of the teenage brain.

"Our research introduces a new set of questions about what it means to speed up the aging process in the brain," Kuhl said. "All the best research raises profound new questions, and I think that's what we've done here."

Is there a health problem that's worrying you? Do you have a question about COVID-19? Let us know via health@newsweek.com. We can ask experts for advice, and your story could be featured in Newsweek.

Reference

Corrigan, N.M., Rokem, A., Kuhl, P.K. (2024). COVID-19 lockdown effects on adolescent brain structure suggest accelerated maturation that is more pronounced in females than in males. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2403200121

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.