Stargazers hoping to see the Orionid meteor shower light up the sky next week may be disappointed this year, due to the interference of another astronomical body.

The Orionids are due to peak on October 21 and be at least somewhat visible between September 26 and November 22, and can result in around 23 meteors per hour in moonless skies, according to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA).

This year, however, the shooting stars might be drowned out by the light of the moon, which is expected to be nearly entirely full.

On October 20 and 21, the moon will be around 80 percent full. Additionally, the moon will rise between 8 and 10 p.m. across the United States on these nights and stay high in the sky for the entire night.

Meteor showers are easier to see in darker conditions because meteors are typically faint streaks of light that stand out against a dark background. A fuller moon makes it harder to see meteor showers because its brightness illuminates the night sky, reducing the contrast between the dark sky and the meteors.

"The sky as a whole is about 40 times brighter during a full moon than it is at new moon," Brad Gibson, director of the E.A. Milne Center for Astrophysics at the United Kingdom's University of Hull, previously told Newsweek.

"Considered to be one of the most beautiful showers of the year," according to NASA, this shower is named for the constellation Orion, which is where the meteors appear to originate in the sky. During the peak, Orion will be highest in the sky at around 2 a.m., and will be visible in both the Southern and Northern Hemispheres. However, the meteors can appear anywhere in the sky, and NASA suggests that looking about 45 to 90 degrees away from Orion will reveal longer and more spectacular meteors.

Orionid meteors fall to Earth at immense speeds of around 41 miles per second and may occasionally become bright fireballs or leave glowing trails.

To catch the best glimpse of these meteors despite the moon's glare, NASA advises going somewhere far from city lights or street lamps, and staying off your phone for around half an hour to allow your eyes to adapt to the dark.

"Come prepared with a sleeping bag, blanket, or lawn chair. Lie flat on your back with your feet facing southeast if you are in the Northern Hemisphere or northeast if you are in the Southern Hemisphere, and look up, taking in as much of the sky as possible," NASA explains on its website.

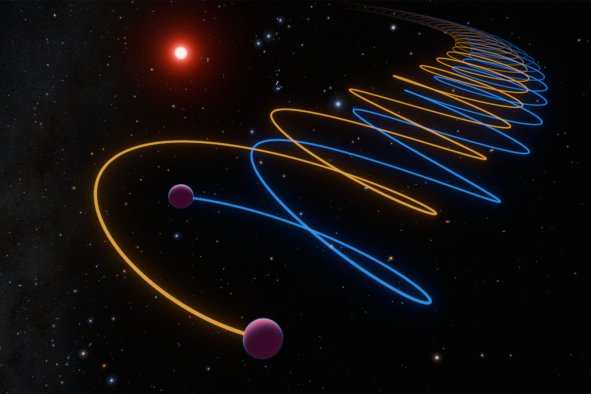

The Orionids are caused by our planet passing through a path of debris left behind by Halley's Comet also known as comet 1P/Halley. As the comet approached the sun once every 76 years, it sheds dust and rock in its wake, which the Earth intersects with twice a year, in October and May. In October, this causes the Orionids, while in May, it sparks the Eta Aquariids meteor shower.

When this debris falls into our atmosphere, it burns up, creating the shooting lights we know as meteors.

"As [comets] orbit close to the sun, the heat causes the ice to vaporize and release dust and small rocky particles. And this debris spreads along the comet's orbit, forming a trail. When Earth passes through this trail, the particles enter our atmosphere at high speeds, burning up and creating visible streaks of light – this is what we call a meteor shower," Minjae Kim, a research fellow in astronomy and astrophysics at the University of Warwick, previously told Newsweek. "The intensity of a meteor shower can be determined by the density of the debris and Earth's path through it."

Do you have a tip on a science story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about meteor showers? Let us know via science@newsweek.com.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.