Paleontologists have revealed a "remarkable" prehistoric creature that has been "spectacularly preserved" by fool's gold—a common name for a substance called iron pyrite.

The newly identified species, named Lomankus edgecombei, lived around 450 million years ago, a study published in the journal Current Biology reports.

"There are lots of types of exceptional preservation, but preservation in pyrite of this kind is extremely rare. In the last half a billion years there are only a handful of examples," study lead author Luke Parry with the Department of Earth Sciences at the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom told Newsweek.

The deep-water species belongs to a group of animals known as arthropods—an incredibly diverse group of invertebrates with jointed limbs and a hard shell known as an exoskeleton, which includes arachnids, insects and crustaceans, as well as extinct animals like trilobites. Lomankus edgecombei is distantly related to spiders, scorpions and horseshoe crabs.

Lomankus was described based on five specimens originally found in New York State by a fossil collector. The collector subsequently donated three of the specimens to the Yale Peabody Museum. Parry saw the specimens in 2019 when he was a postdoc at the university.

"I was pretty blown away by how well-preserved they were," Parry said.

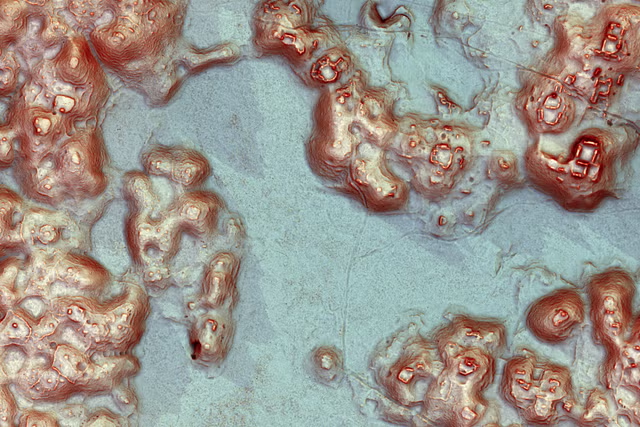

The extraordinary creatures were preserved by pyrite, a shiny mineral that resembles gold in appearance but has different properties. Its metallic sheen and pale yellow color make it easy to mistake for real gold.

"As well as having their beautiful and striking golden color, these fossils are spectacularly preserved. They look as if they could just get up and scuttle away," Parry said in a University of Oxford press release.

The fossils originate from the famous Beecher's Trilobite Bed—a sedimentary deposit in New York that contains numerous exceptionally well-preserved trilobites. These prehistoric marine animals resemble roly-poly bugs, featuring a segmented body, half-moon-shaped head and several limbs.

Beechers is renowned for its "golden" trilobites, which have also been preserved in pyrite like Lomankus. Other organisms are only rarely preserved in the deposit, highlighting the rarity of the newly described fossil creature. It would have lived in a deep water, oxygen-poor environment that was also very dark.

The Lomankus fossils were preserved thanks to a process known as pyritization—a type of fossilization where organic material is replaced by pyrite over time. Most commonly seen in marine fossils, such as ammonites or trilobites, pyritization can produce highly detailed, metallic-looking fossils that are both scientifically valuable and visually striking.

"Although pyrite forms very commonly today in fine-grained marine rocks, pyritization of soft parts of organisms is very rare indeed because you need a special set of conditions for it to replace parts of a carcass," Parry told Newsweek. "In life, Lomankus would have been soft—sort of like a shrimp or prawn—and not hardened with biominerals like a trilobite. If pyrite hadn't replaced all of these soft parts, then they would have decayed away, and we would have no fossils at all."

"Pyrite forms today through the action of sulfate-reducing bacteria that break down organic material in the absence of oxygen and produce hydrogen sulfide. This can then react with iron to form pyrite, which is iron sulfide. So, to form pyrite, you need organic material, iron, and a lack of oxygen."

The sediments that contain the fossils are low in organic material but high in iron, so the carcasses of the animals were like small islands where the conditions for pyrite to form are just right, according to Parry.

"The specimens of Lomankus would have been buried alive in a kind of submarine landslide called a turbidite, and so this rapid burial ensured that no decay had taken place before they were buried," he said.

"These remarkable fossils show how rapid replacement of delicate anatomical features in pyrite before they decay, which is a signature feature of Beecher's Trilobite Bed, preserves critical evidence of the evolution of life in the oceans 450 million years ago," study co-author Derek Briggs with Yale University said in the press release.

Lomankus belongs to an "iconic" subgroup of extinct arthropods called megacheirans that had a large, modified leg at the front of their bodies designed to capture prey. This feature has been dubbed a "great claw" or "great appendage."

Megacheirans like Lomankus were very diverse in the Cambrian Period (538-485 million years ago) but are thought to have been largely extinct by the Ordovician Period (485-443 million years ago)—with only two possible later occurrences in the fossil record.

"Lomankus is about 50 million years younger than most megacheiran," Parry told Newsweek. "It looks strikingly similar to a fossil called Leanchoilia from the Cambrian, except the long spines forming the claws at the end of the great appendage just aren't there, suggesting that it was using the appendage for something quite different—probably sensing the environment. This shows that megacheirans continued to do new things long after the majority of them went extinct."

The latest study also sheds light on a long-standing paleontological mystery. Scholars have debated exactly what the equivalent of the great appendage is in living species.

It has been suggested that it has a common origin with the mouthparts of spiders and horseshoe crabs—known as the chelicera. Alternatively, it could be an appendage that modern arthropods do not have but is present as an antenna in a group of close relatives called velvet worms or onychophorans.

"We find an arrangement of features in the head, including a plate over the mouth, that is consistent with the arrangement of head features in other arthropods, suggesting that the great appendage is the same thing as the chelicera of horseshoe crabs and spiders," Parry said.

Do you have an animal or nature story to share with Newsweek? Do you have a question about paleontology? Let us know via science@newsweek.com.

Reference

Parry, L. A. (2024). A pyritized Ordovician leanchoiliid arthropod. Current Biology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2024.10.013

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.