Three of the oldest stars in our universe have been discovered, and they were lurking right under our noses this whole time, and traveling in the wrong direction

The heavenly bodies were detected by MIT researchers in the "halo" of stars that surrounds the distant edge of our Milky Way galaxy, and are thought to have formed between 12 and 13 billion years ago, according to a new paper in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

"Interestingly they're all quite fast—hundreds of kilometers per second, going the wrong way," study co-author Anna Frebel, an MIT professor of physics, said in a statement. "They're on the run! We don't know why that's the case,"

The universe itself is thought to be around 13.8 billion years old, and our own sun is only 4.6 billion years old, making these stars some of the oldest in the cosmos.

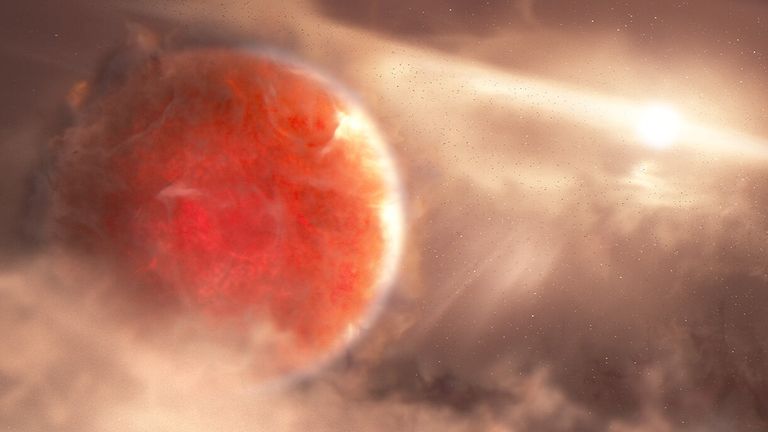

These stars, dubbed SASS (Small Accreted Stellar System stars), are suspected to have been born when the very first galaxies in the universe were forming, with each belonging to its own small primordial galaxy.

These galaxies are thought to have then been absorbed into the growing Milky Way, with these SASS stars being the last survivors of their original galaxies.

The stars are situated about 30,000 light-years from Earth in different locations in a cloud of stars that shrouds the outer edges of the Milky Way. Three other ancient stars were also discovered by the researchers in the paper, but these were found to be slightly younger.

"These oldest stars should definitely be there, given what we know of galaxy formation," added Frebel. "They are part of our cosmic family tree. And we now have a new way to find them."

The Big Bang Theory is the leading explanation about how the universe began. At its simplest, it talks about the universe as we know it starting with a small singularity, then inflating over the next 13.8 billion years to the cosmos that we know today.

As the universe expanded, it also cooled, eventually enough to allow for the formation of subatomic particles, and later simple atoms. Mostly hydrogen and helium were formed in the first few minutes after the Big Bang.

The earliest stars in the universe would therefore have been made up of very little else except hydrogen and helium, as heavier elements like strontium and barium simply hadn't been created in high enough quantities—these elements are forged in the hearts of stellar supernovas.

Therefore, stars that have low abundances of strontium and barium in their light spectra may be some of the earliest in our universe.

These three ancient stars had originally been observed by the Magellan telescope between 2013 and 2014, and showed a very metal-poor spectrum, but hadn't been analyzed in detail yet. The researchers then determined that these stars may indeed be between 12 and 13 billion years old, and that their chemical makeup matched those seen in some extremely old dwarf galaxies.

This, paired with the discovery that the stars appear to be moving around the galaxy in the opposite direction to most other stars, indicates that they may have originated elsewhere and been dragged into the Milky Way.

"The only way you can have stars going the wrong way from the rest of the gang is if you threw them in the wrong way," Frebel said.

The researchers then looked at other known ancient stars and saw that many of them too moved in this retrograde motion around the galaxy, traveling in the wrong direction, a key aspect. "It was the piece to the puzzle that we needed, and that I didn't quite anticipate when we started," added Frebel.

They hope to find more ancient SASS stars by looking for metal-poor stars that are traveling in the opposite direction to most other stars. They also hope that they can use these SASS stars to study the history of the dwarf galaxies that they came from.

"Now we can look for more analogues in the Milky Way, that are much brighter, and study their chemical evolution without having to chase these extremely faint stars," Frebel said.

Do you have a tip on a science story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about stars? Let us know via science@newsweek.com.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.